Image credit: Pexels

In a Manhattan federal court, the drama unfolded over two days of testimony, with Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev leveling serious accusations against the renowned auction house Sotheby’s. He charged them with collusion alongside Swiss art dealer Yves Bouvier. The claim? That they swindled him out of hefty sums in art dealings. This gripping testimony peeled back the curtains on the art world’s often murky processes, processes that Rybolovlev insists led to his significant financial losses. He recounted his trust in Bouvier, once considered almost like family, now a central figure in this high-stakes legal battle.

Once valued at a staggering $7 billion, Rybolovlev’s lawsuit against Sotheby’s seeks redress for losses exceeding $160 million. The crux of his legal argument? Bouvier’s alleged scheme of purchasing artworks from Sotheby’s, only to sell them to Rybolovlev at massively marked-up prices. This was all part of Rybolovlev’s grand ambition to amass a premier art collection, a venture in which he poured over $2 billion from 2002 to 2014.

During the cross-examination, Sotheby’s counsel brought out that Rybolovlev trusted his advisors and did not insist on seeing records that would have revealed where his money ended up. Even when he spent tens of millions of dollars on artwork, Rybolovlev acknowledged that he did not scrutinize the acquisitions.

Rybolovlev blamed his financial losses on the conduct of the biggest corporation in the market, Sotheby’s, highlighting how hard it is for seasoned corporate clientele like himself to spot fraud. He said Sotheby’s was obligated to alert him as they knew or should have known about the purported scam.

In response, Rybolovlev said he was not just suing Sotheby’s for financial gain but also because he believed more openness in the art market was essential. He expressed worry that clients suffer serious difficulties when a key sector player acts this way.

During the trial’s opening statement, Sara Shudofsky, Sotheby’s attorney, refuted these allegations, claiming that Rybolovlev is trying to hold an innocent individual accountable for the deeds of others. Daniel Kornstein, Rybolovlev’s attorney, charged Sotheby’s with acting out of greed and participating in a complex scam.

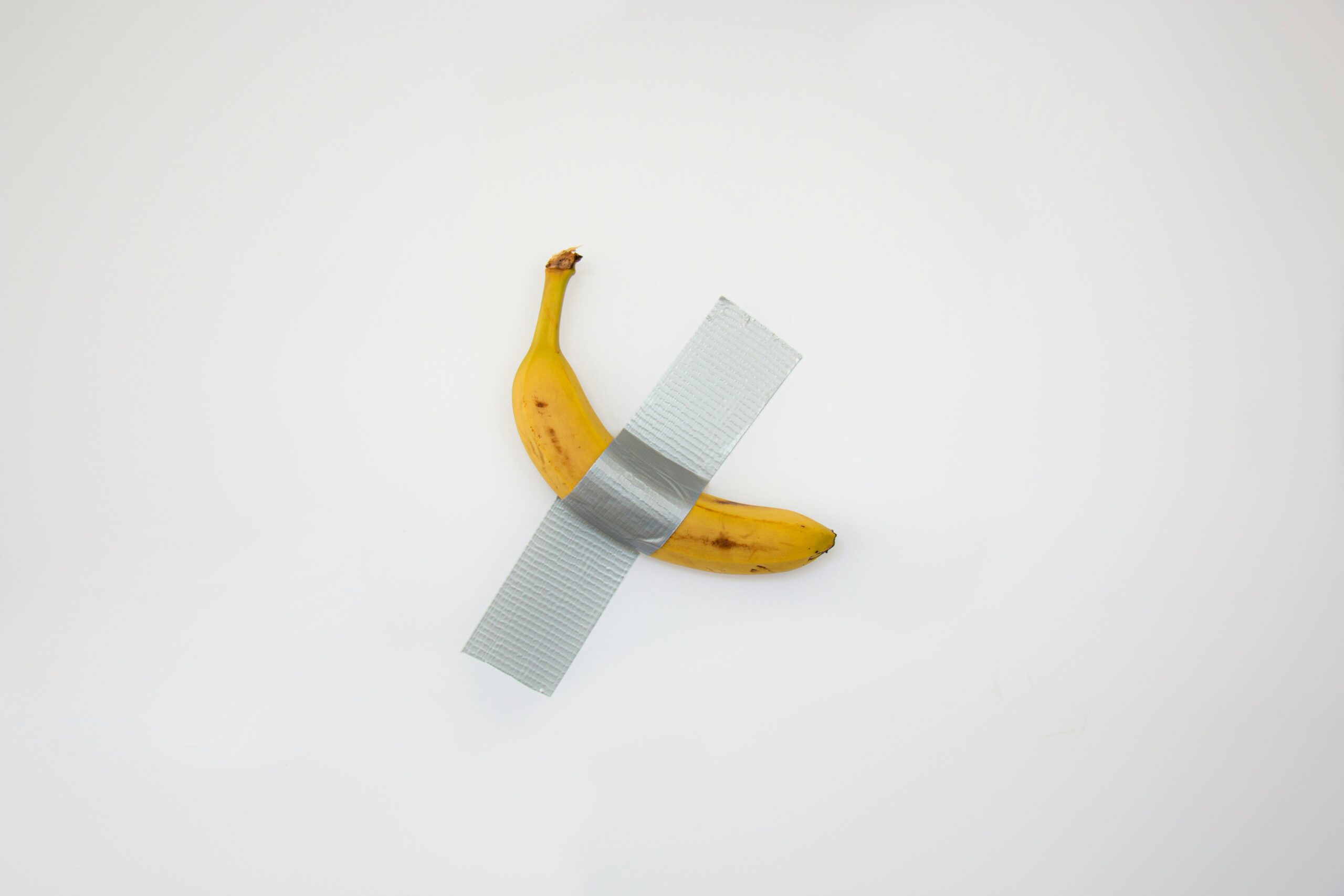

The trial centers on four works of art, one being the well-known “Salvator Mundi” painting by Leonardo da Vinci. Rybolovlev’s legal team claims Bouvier paid $83 million for the artwork from Sotheby’s and then sold it to Rybolovlev for more than $127 million the next day. The painting, which Rybolovlev sold through Christie’s in 2017 for a record-breaking $450 million, became the most expensive painting ever sold at auction.

When Bouvier reached an undisclosed settlement with Rybolovlev in December, the legal processes took an unexpected turn. David Bitton and Yves Klein, Bouvier’s Swiss attorneys, angrily refuted fraud claims, claiming that Bouvier’s lawsuits had been dropped in several states, including Singapore, Hong Kong, New York, Monaco, and Geneva.

There was news of Rybolovlev’s inclusion on a list compiled by the Trump administration of 114 Russian billionaires and politicians connected to Vladimir Putin. It was made clear, nevertheless, that he had not resided in Russia for thirty years. Kornstein told the jury that his client, a former doctor who went into business, was not on the list of Russian billionaires blacklisted following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The trial is taking place in the context of high-stakes legal disputes and allegations made by members of the art market’s elite circles, which raises concerns about the need for more accountability and transparency in the sector. The verdict in this case might significantly impact how art sales are handled and overseen going forward.