Image credit: Unsplash

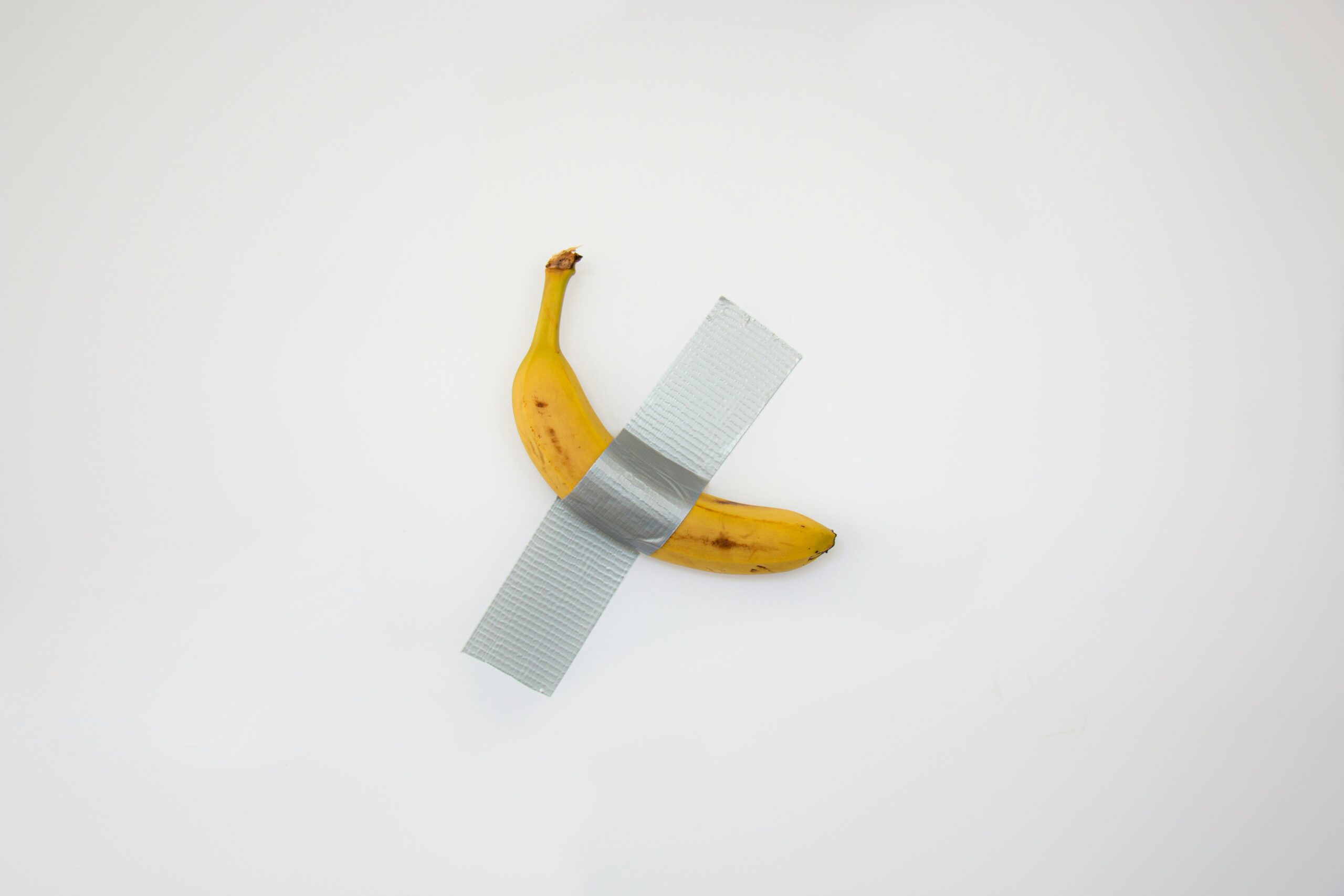

In November, Maurizio Cattelan’s provocative duct-taped banana sculpture Comedian (2021) captured attention when it sold for $6.2 million at Sotheby’s in New York. While the wider world thought it absurd, it became emblematic of other issues plaguing the art world. The auction season, which spans 15 live sales at South Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and Phillips, raised $1.3 billion. However, that’s a steep 41% drop from the previous year’s figures.

A Market in Decline

The art market has suffered a prolonged slump over the past two years. Political uncertainty following the US presidential election and declining enthusiasm among the ultra-wealthy have compounded these challenges.

Although a boost in stocks, cryptocurrencies, and the dollar post-election hinted at renewed interest, auction results told a different story. Many works sold at or near the estimated value with few bids, while others failed to sell.

“Supply constraints, reduced auction volume, fewer top-tier lots, and a notable decline in third-party guarantees all indicate a softening environment,” Christine Bourron, CEO of Pi-eX, said.

Third-party guarantees, which once buoyed auction prices, dropped from 71% of total sales value in 2023 to 50% in 2024.

Trophy Pieces Still Shine

Despite the overall downturn, standout pieces generate excitement. Sotheby’s auctioned works from the late Sydell Miller’s estate, including Claude Monet’s Nymphéas (circa 1914-17), sold for $65.5 million. While not among Monet’s most celebrated works, it demonstrated the enduring appeal of established names.

René Magritte’s Empire of Light (1954) also attracted attention as the centerpiece of Christie’s sale of Mica Ertegün’s collection. Widely regarded as one of Magritte’s finest works, it fetched $121.2 million. The purchase set an auction record for the artist. However, with only two bidders competing for the piece, some experts questioned whether the result reflected waning interest, even among billionaires.

The Decline of Emerging Artists

The speculative frenzy surrounding younger artists has also cooled. Sotheby’s The Now sale, which focuses on contemporary art, yielded just $16.5 million from 10 lots. That’s a sharp decline from the $72.9 million generated by 23 slots in 2022. High-profile names like Flora Yukhnovich and Amoako Boafo were absent, while works by Avery singer and Christina Quarles failed to sell.

A Brussels-based collector, Alain Servais, attributed the downturn to rising interest rates and a slowing Chinese economy.

“The rocket fuel propelling them was free money and Asian demand. Those two engines stopped brutally,” he said.

Shifting Priorities for the Wealthy

Art is no longer a “must-have” for the younger international elite. “It is still a must to be seen at Frieze and Art Basel, but it is more like a need to attend, not to own,” Roman Kräussl, a professor at Bayes Business School, said.

This attitude reflects broader changes in how the wealthy perceive art.

David Kusin, a Dallas-based art economist, echoed the sentiment, describing art as a “problematic investment of passion.”

When adjusted for inflation, the long-term decline in arts aggregate value dropped 23% since 1988.

“It is not a two-year sales slump. It is a slow-motion, generation-long problem,” Kusin said.

The Role of Cryptocurrencies and Speculation

Cryptocurrencies offered a glimmer of hope during the November auctions, particularly in the case of Comedian. At least four of the seven bidders for the sculpture were known crypto investors, and the work’s success coincided with the launch of a meme coin inspired by the banana.

Market analysts suggest that President Trump’s proposed tax cuts and deregulation stimulate demand, particularly among the ultra-wealthy in sectors like tech and finance. However, skepticism remains.

One observer asked, “Will they buy art, particularly if it doesn’t have an attached meme-coin?”

Art Collecting in an Uncertain World

The art market’s woes highlight a fundamental shift in priorities for the global elite. Serious art collecting has traditionally thrived in stable, affluent democracies, but today’s geopolitical and economic instability has relegated it to the periphery.

“In a world with less stability, collecting art drops down the to-do list, even for the super-rich,” David Kusin said.