Image credit: Pexels

In the elite sphere of art sales, a contentious legal dispute is taking shape. Russian tycoon Dmitry Rybolovlev has leveled serious accusations against the prestigious auction house Sotheby’s, alleging their participation in a fraud scheme. Rybolovlev claims this supposed involvement led to his significant financial setbacks on artworks by luminaries such as Amedeo Modigliani and Leonardo da Vinci. Sotheby’s, on the other hand, staunchly refutes these allegations, maintaining their innocence in a court battle where the financial implications run into tens of millions.

The defense from Sotheby’s, articulated by attorney Sara Shudofsky, argues that Rybolovlev is unfairly trying to pin the blame for his miscalculations on them. Shudofsky highlights that Rybolovlev, an astute businessman with a history of successful endeavors, neglected basic due diligence in his art purchases, a responsibility he should personally shoulder. She asserts that Sotheby’s was completely unaware of and uninvolved in any purported fraudulent activities.

Rybolovlev’s lawyer, Daniel Kornstein, insists that Sotheby’s executives, including one based in London, were complicit in an elaborate fraud that allowed the auction house to profit substantially. Rybolovlev, known for acquiring a Palm Beach mansion from Donald Trump for $95 million, is expected to testify. The case revolves around the $2 billion he spent between 2002 and 2014, acquiring a remarkable art collection through his companies: Accent Delight International Limited and Xitrans Finance Limited. His reliance on art broker Yves Bouvier, who claimed to save him money through a 2% commission, led to accusations of fraud against Bouvier.

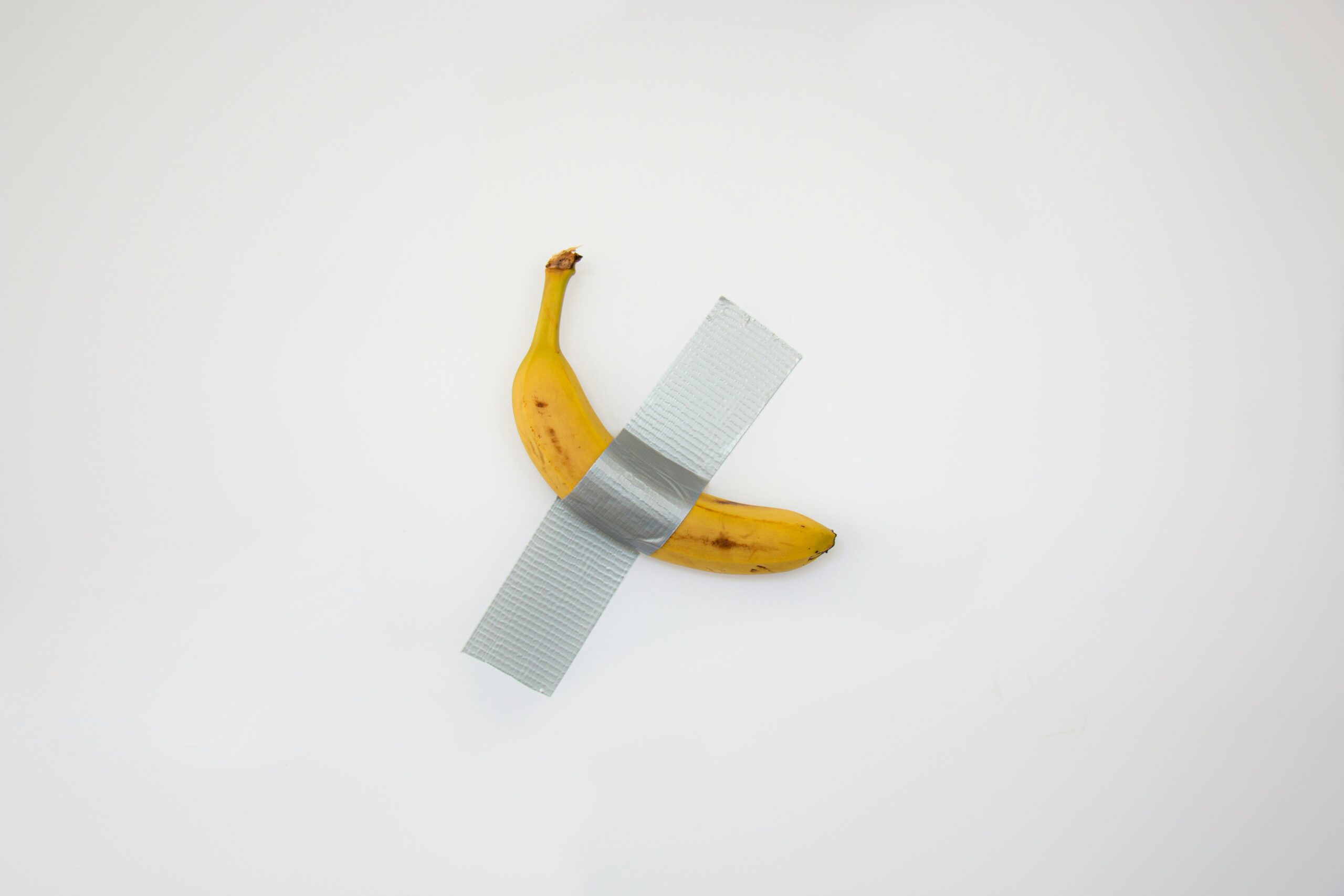

Kornstein portrays Bouvier as a trusted friend turned con man, responsible for substantial markups on art purchased from Sotheby’s before selling it to Rybolovlev. The lawyer argues that Sotheby’s was aware of these activities, suggesting the auction house participated in the fraud for financial gain. The trial delves into the specifics of art transactions involving works by prominent artists, including Picasso’s “Homme Assis au Verre” and da Vinci’s “Salvator Mundi.” The latter, bought by Bouvier for $83 million and resold to Rybolovlev for over $127 million, became the most expensive painting ever sold at auction in 2017, fetching a historic $450 million.

Amidst legal entanglements, Bouvier has consistently denied allegations of fraud. His lawyers cite global authorities rejecting the charges, including cases discontinued in Singapore, Hong Kong, New York, Monaco, and Geneva. A settlement between Bouvier and Rybolovlev under undisclosed terms adds another layer to the legal saga. As the trial unfolds, it brings to light the intricate dynamics of high-profile art dealings, exposing the vulnerabilities in an industry reliant on trust. The verdict may have far-reaching implications for auction houses and art enthusiasts involved in multimillion-dollar transactions, redefining the operations of high-value art acquisitions and sales. The case’s complexity is further heightened by the continuous denial of fraud allegations, with Bouvier’s legal team pointing to the fact that global authorities have dismissed charges across various jurisdictions.

As the legal proceedings continue, the trial offers a glimpse into the multifaceted world of high-profile art dealings, emphasizing the pivotal role of trust in an industry where reputation is of the utmost value. Beyond the financial stakes, the verdict may reshape the future of high-value art transactions, influencing the practices of auction houses and shaping the expectations of art enthusiasts engaged in multimillion-dollar acquisitions and sales from here on out.